Dushanbe, Tajikistan

July 8th

3750 km from Urumqi

It's a strange feeling to be sitting in a modern Internet cafe with a full belly after a hungry month spent in some of the poorest, most remote country I have ever been in. It's been a tough, eye-opening, unforgettable ride through the remote Pamir Plateau and along the long Tajik-Afghan frontier, and I have to say that I'm enjoying taking a couple of days off the bike to eat, relax and sleep.

When I last wrote a month ago, I was in Jalalabad. After a day off there, punctuated by a visit to the very archetype of a decaying Soviet hot-spring sanatorium, I rode to Osh, the second-largest city in Kyrgyzstan. Because of the ridiculously convoluted nature of the border with Uzbekistan, rather than 40 flat kilometres as it would have been in Soviet times, the ride was 110 undulating kilometres long. I stopped halfway to see some 11th-century Muslim mausolea in Ozgon, the first really impressive old architecture I've seen since Urumqi. Osh was big and clamourous and full of good food. I spent a great deal of time in the big open-air food court opposite my hotel, filling my belly with kebabs and borshch against the lean times ahead. I was still waiting for Antoine to reappear from his visa run to Bishkek; he was 2 days late in returning. While waiting, I treated myself to a haircut, which was an amusing experience, with the barber constantly sending for items from the women's hair salon upstairs. The final results weren't too bad, and, at $1, neither was the price. I checked my e-mail again and read that Antoine had arrived in Osh and cycled off down the road looking for me. I set off in hot pursuit, only to discover that nobody along the road had seen him. 60 kilometres down the road he passed me as a passenger in a truck which then refused to stop and let him out. We didn't find each other until mid-morning the next day.

The ride south from Osh was through the northern outliers of the Pamir mountains, over a couple of high passes. The riding was enjoyable, and the scenery was impressive, but on the third day out of Osh, I made an unwelcome discovery. My rear wheel began wobbling badly, and when I investigated, I discovered that the frame of my bike, worn out by 19,000 kilometres of hard riding, had snapped beside the back axle. I was unhappy, but I had bought a bike made of steel rather than aluminum at least partly because steel can easily be welded together again if it breaks, so I knew that all I needed to find was a welder. By sheer chance, when I stopped a passing car, he was going to a nearby village off the main road where there was the only welder between myself and the Tajik border. I piled into his Lada and in an anxious half hour, the bike was in one piece again, reinforced by an extra steel plate, and the future of my bike odyssey was rosy again.

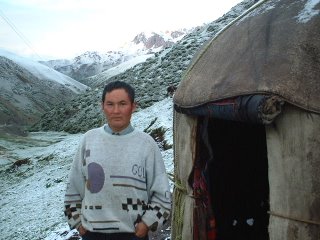

That afternoon, as Antoine and I slogged uphill to a 3600-metre pass, the weather, which had been spitting for a couple of hours, settled into steady rain which got colder as we gained altitude. At the foot of the final climb, it turned to snow and we decided to seek shelter, chilled to the bone, in a nearby yurt. We spent the night snug and warm in this quintessentially Central Asian felt tent, fed endless cups of tea by the mother and son who were inhabiting the yurt for the summer as they grazed the family flocks on the high pastures. We had an evening of interesting discussions on the role of bribery in Kyrgyzstan (epidemic at all levels, especially in education), bride-stealing (a common way to get around paying high bride-prices, by kidnapping the bride-to-be and negotiating from a position of strength) and, inevitably, the lament that "things were better back in Soviet times". As we drifted off to sleep, the mother asked Antoine and I why we aren't married, and cackled that she would find us both Kyrgyz brides.

The next day, my last in Kyrgyzstan, was easily the most disappointing of my stay. We crawled over the top of the pass in brilliant sunshine, surrounded on all sides by snowy peaks, and descended briefly into the high-altitude Pamir Alay valley, a broad green swath between the mountains we had just crossed and the wall of monstrous 6500-metre peaks to the south dominated by 7000-metre Peak Lenin. To the east the valley leads, over a couple of easy passes, to Kashgar, China, while to the west the direct road to Dushanbe stretches arrow-straight to the horizon. We rolled into Sary Tash, the last village in Kyrgyzstan, in a happy mood, stopping frequently for photos of the dazzling white glaciers in front of us.

We wanted to do only a few things in Sary Tash: eat well, buy some extra food supplies and change our leftover Kyrgyz som into Tajik somoni. None of these things really occurred. The town's three cafes were almost bereft of food, and there was nothing to buy except vodka, which the entire local population had been hammering back all morning. I had two aggressive drunks try to pick fights with me, the local kids (several of whom seemed to have been sniffing gasoline) threw rocks at us and someone stole my wallet (which, luckily, contained only $0.30 in local currency at the time). We left before things turned into a full-scale brawl and headed across the Alay valley, past dozens of huge golden eagles quartering the grasslands for rodent tidbits, to the Kyrgyz immigration post. There, it was a repeat of Sary Tash. The border garrison were out playing volleyball and toasting each point with vodka. The two soberest officers decided that my visa was not in order: "Shee, it shays good until the 15th; you're too late!" "But it's the 15th today." "That's what we mean; you're too late." And so on for 2 interminable hours. We were clearly in the right, but it's hard to argue with a lot of armed drunks looking for bribes. The situation was saved by the Euro 2004 soccer tournament; everyone wanted to go back to Sary Tash to watch the game, and they couldn't just leave us sitting there, so they finally sent us on our way at dusk. We camped in a shimmering meadow alive with wildflowers, wondering what Tajikistan would be like.

The next day we crawled uphill over a 4200-metre pass, the Kyzyl-Art, into a new world. Gone were the greens and the life of the Kyrgyz mountains. Instead, after a long session of tea and bread at the Tajik immigration post, we bumped downhill into a passable imitation of Mars: not a blade of vegetation or a drop of water to be seen. The road, the 1930s-era Pamir Highway built by the Soviets, was empty; we saw 2 vehicles that day, and camped beside the deserted road feeling very, very insignificant in the vast landscape.

For several days we crawled south to the first town, Murgab. The views would have been spectacular if it hadn't been so cloudy and grey all the time, punctuated by rain and hail. For a region which looked so arid, it certainly rained a lot. Having brought rain to the Sahara and the Atacama deserts in the past, I seemed to be strengthening my credentials as a rain god. The landscape was almost entirely empty of human life until we got near Murghab. The Eastern Pamirs are inhabited by 15,000 Kyrgyz nomads, half of whom live in Murghab and the rest of whom live in the broad, flat valleys between the barren brown mountains. It reminded me a great deal of Western Tibet, although not quite as grand and open and impressive, althought that may have just been the grey weather. In particular Lake Karakul, which is said to be absolutely spectacular, looked very subdued in mist and rain.

In Murghab we waited for 2 days for our border zone permit, an arcane piece of Soviet-era movement control, before setting off into the rain. We decided to strike off into the remoter corners of the Pamirs, trying to reach Lake Zorkul, the source of the Oxus, by a back road. We started off well on a dirt track leading to a hunting camp where well-heeled Americans come to shoot endangered Marco Polo sheep. (The locals poach plenty of them too, borrowing automatic weapons from the border guards and selling the meat at half the price of yak meat or mutton; a tasty stew we had at Karakul turned out, afterwards, to be Marco Polo sheep, not yak.) The inevitable snow and hail came, though, turning the track into a quagmire. The next morning we ventured further, but finding a couple of Dushanbe expatriates in a jeep irremediably augured into the mud at a river crossing convinced us that the road was only going to get worse, and we fled back to the main road the following morning.

For a couple of days we rolled through slightly more populated country, the flat boggy Pamir valleys dotted with Kyrgyz yurts, before striking off again onto a secondary road for the Afghan border. We bumped along a lamentable dirt road to a 4000-metre pass and weathered a blizzard that night. We spent a couple of days descending very slowly along the Pamir river (the infant Oxus), watching Afghanistan roll past us on the opposite bank a stone's throw away. (I pitched a couple of rocks across the river into Afghanistan just to show it could be done.) The weather continued to be miserable, and we spent the night in an abandoned road maintenance house, listening to the gale outside try to blow us back to the pass. In the morning, shaggy Bactrian camels were roaming the Afghan bank of the river, looking like a throwback to the days of the Silk Road

When we finally dropped into flat country at the junction of the Pamir and Wakhan rivers, we thought that our troubles were over. The weather was warmer, and there were villages strung densely along the river. We were on a major ancient trading route along which Marco Polo himself had come, and old forts and Buddhist monasteries lay in ruins along the river. Instead, when we asked in the first town, Langar, where we could find a cafe, we were told "not here." A store selling food? "Nope." Gasoline? "Maybe 15 kilometres down the road?" For several days, on the worst roads we'd seen yet, rutted gravel traps interspersed with sand dunes or boulder fields, it was the same story: no food, no gasoline (our camping stoves were running empty), no cafes. It was the most cash-poor place I'd been in years, poorer even than most of Tibet; everyone was a subsistence farmer, with no money to spend, and hence no shops or bazaars in which to spend it. People live on black tea and bread and nothing else; hardly a diet to subsist on, let alone ride a bike on. We resorted to asking random farmers if they had any bread to sell us, as otherwise we would have starved. Even the flour for the bed is largely a handout from the World Food Program; truly, this corner of Tajikistan makes most of Africa look rich. It's a measure of how poor Afghanistan is that the Tajiks we talked to said that it was a pity that life was so much rougher over on the Afghan side of the border.

Things began to look up as we approached the town of Ishkashim. One hungry morning, we stopped in a small village and found, wonder of wonders, a cafe. We went in and ordered a dozen fried eggs, bread and whatever else the owner could find to feed us. We had eaten and were just contemplating leaving when four drunks walked in. One of them introduced himself as a cop and demanded to see our papers. Another endless argument ensued, as he tried to convince us that our border permit was not in order (it was) and that he was going to have to arrest us. I impressed myself first of all by being able to argue our case for 2 hours in Russian, and secondly by not losing my temper and throwing the idiot into the river, where he richly deserved to end up. The funny thing was that when he finally caved in and let us go, he sent all the spectators out of the room so that nobody would see him climb down. We saw him again two days later, past Ishkashim, sober and in uniform at a checkpoint, and he betrayed not a hint of recognition. I felt lucky that we, as foreigners, were able to stand up to this sort of official bullying. It must be tough if you're Tajik and have to live in the same village as this lout; if you stand up to him, you always have to worry that he'll exact some sort of revenge later.

The miserable, slow, bumpy riding and empty stomachs were somewhat compensated by two things. First of all, on the Afghan side of the river, we could see the high, steep, ice-sculpted peaks of the HIndu Kush, marking the Afghan-Pakistani border; Afghanistan is only 20 kilometres or so wide at this point, the funny-looking finger of the Wakhan corridor which separates the former British and Russian empires from each other. I had seen these peaks before, in 1998, from the other side, and I had forgotten how dramatic they are, much more so than the older, rounder, gentler peaks of much of the Pamirs. Huge glaciers spill down steeply from them, practically right into the Pyanj River. The other nice thing about the area were the hot springs, a welcome place to warm up and get clean and relaxed after a tough day in the saddle.

The people had changed when we dropped off the Pamir Plateau, from the Mongol-looking Kyrgyz to the European-looking Pamiri Tajiks. Ismaili Muslims, descendants of ancient Indo-Iranian tribes, the Pamiris would not look out of place in Greece or the Balkans, and indeed myth makes them the descendants of Alexander the Great's soldiers, although they've been in the area much longer than that. Each valley's people look distinctly different, and speak a completely different language. Some people looked very Indian, while other valleys were full of sandy-haired people who wouldn't have looked out of place in an English pub.

The ride to Ishkashim and on to Khorog was fairly uneventful, marked only by frequent encounters with Russian border guards. Much more professional than their Tajik counterparts, the Russians were deeply suspicious of what we were doing prowling around the Afghan frontier, but were mollified when all our papers were in order. They were also always sober when on duty, a welcome change.

In Khorog, we found cherry, apricot and mulberry trees bearing ripe fruit, and a bazaar worthy of the name. We thought that the hard part of our trip was over. Instead, the road deteriorated further after that point, making each day a dismal series of bumpy uphills and downhills, dodging potholes that could swallow a Lada. Once again the cash economy seemed to disappear, and the villages clinging to mountainsides grew poorer. We stayed in people's houses several times and discovered that this was the only way to eat well; none of this good food was available in stores or cafes. On the opposite bank of the Oxus, we could see the World Food Programme handing out free flour and men carrying 50-kg sacks of it dozens of kilometres along precipitous, death-defying trails hacked into the mountainsides.

No bike trip in Asia is complete without being arrested, and one day, coincidentally on Canada Day, at a (luckily) Russian checkpoint, we found that our border zone permit had expired the day before. It took 6 hours to sort out the mess, with us being sent to the district border garrison and then to the local visa office to extend our permits. It worked out well, though; we were fed twice, and a jeep took our luggage to the Vang garrison while we biked unencumbered by baggage for 25 kilometres. Even our endless wait for the permit to be extended was made bearable by the fact that the office was surrounded by cherry trees groaning under a load of ripe fruit, and we ended the day swimming in the garrison swimming hole.

Crossing the 3200-metre pass away from the Oxus, I fell ill with dysentery, making the crossing a slightly delirious, hazy experience. Antoine, ill as well, took a truck, and then jumped another one to get to Dushanbe and off this road of hopelessness as quickly as possible. Even the truck, though, took 2 days to make the final 200 km into the city, and he beat me into town by only 6 hours. I soldiered on, riding my bike over the worst roads I've ever seen outside of Tibet, before suddenly hitting asphalt 70 km from town and zipping into this oasis of properity in the desert of utter poverty that is Tajikistan.

I'm staying here with Monika (one of the expats we found stuck in the river near Murghab) and her husband Sebastian, in their comfortable house. After 2 months on the road, it's almost unimaginable luxury to have a real bathtub, a real toilet, a well-stocked refrigerator and a quiet, walled garden in which to relax. It will be very hard indeed to tear myself away and start pedalling the golden road to Samarkand tomorrow, when (if?) my Turkmen visa is ready, but I really have to start making progress if I'm to arrive in Iran before my Iranian visa expires on July 28th. From now on, the route will lie through more populated areas; the spirit of exploration and adventure will take a back seat to looking at historical monuments, but it's a change which my poor, tired, aching body will probably welcome.