Mashhad, Iran

5300 km from Urumqi

8800 km from Xian

Boiling away again in Turkmenbashiville

Sweating out another kilo of salt

Some people claim Turkmenbashi's to blame

But I know.....it's my own damn fault.

Don't know the reason

I came here in this season

With nothing to see but the hot desert sand

The desert's no beauty

No Saharan cutie

And all I can feel is the heat's leaden hand

(Apologies to Jimmy Buffett)

So here I am in Iran, the last country on this summer's itinerary. It feels as though I've re-entered a Technicolor world after the drabness and depression that afflict the ex-Soviet 'Stans. There's life on the streets, shops are bustling and the roads are more than bustling: they're suicidally busy. I feel as though the hardest work is now over and all I have to do is sweat my way to Teheran over the next three weeks.

When I last wrote, I was in Samarkand. When I emerged from the e-mail cafe that night, I was reminded of what kind of country Uzbekiscam is. The manager of the cafe asked me "What does scammers mean?" I had written in a Messenger conversation that "Uzbeks are all scammers." I didn't think quickly enough to come back with the obvious rejoinder that "I was mistaken; I meant Uzbeks are all scammers or spies for the government." The government keeps a close eye on all communications (Internet cafes monitor all of their users), and dissident opinions can quickly land you in jail, where you are apt to be boiled alive by the secret police. Literally. The US government, which has been propping up President Karimov to the tune of several hundred million a year since 9/11, recently pulled the aid plug because human rights abuses by the security forces are too egregious for even the State Department to continue overlooking. I guess this is what you get from a president who openly admires Timur (aka Tamerlane), the bloodthirsty 14th-century ruler who specialized in constructing pyramids of skulls after sacking a city.

I didn't really like Uzbekiscam that much. Aside from the political situation, everyone seems to be corrupt in some way or other. The ticket sellers at monuments pocket the admission money and don't issue tickets. The airport is full of fixers who aggressively try to help you get a ticket and even more aggressively try to extract huge tips from you. Shops routinely overcharge, and restaurant bills are inflated from the prices originally agreed upon. The traffic cops extort bribes from passing motorists, and hotels charge outrageous sums for rooms (about a month's salary for an average Uzbek). I guess it's because they have had far longer to get used to making their living by fleecing tourists, but it left a bad taste in my mouth (rather like the cold mutton grease that coated my pallate--how do you spell that?--if I didn't wolf down my kebabs quickly enough. In addition, the Uzbeks, more than anyone else so far, are obsessed with money. "How much is your salary? How much does your bike cost? How much is an airplane ticket to Canada? How much? How much?" It becomes wearisome having this conversation every time. Even speaking amongst themselves, the number one topic of conversation seemed to be money and prices. Most Uzbeks lamented how poor their country was, but it looked far more prosperous than Tajikistan or most of Kyrgyzstan. And they certainly got a lot more of my money than the Tajiks did; I spent twice as much money in Uzbekiscam as I did in Tajikistan, in half the time.

The ride from Samarkand to Bukhara was flat, very hot and utterly uninteresting. I reflected, as I rolled through endless cotton fields, that flat countryside is great for putting down big daily kilometre totals, but does nothing for the mind or the soul. I camped halfway in somebody's orchard, and was dragged in for an obligatory breakfast, the sole example of Uzbek hospitality I encountered.

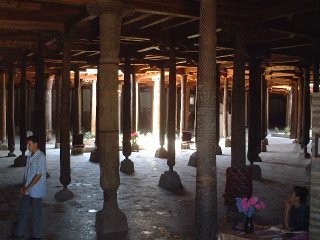

Bukhara, the ancient holy city of Central Asia, was a change from Samarkand. The individual monuments were less impressive than in Samarkand, but the old city as a whole was far more intact and atmospheric. More blue tiles and monstrous mosques and medressas, but also a few older all-brick buildings. I wandered around happily snapping pictures for a couple of days. I ran into more tourists than I'd seen in the previous two months put together; the city was alive with bus tours of Belgians and Dutch and Germans. I ran into Inge and Jarich, a Dutch couple who had cycled from Indonesia, and swapped cycling stories over overpriced beers beside the Labi Hauz pool.

I then had to make an annoying detour to Tashkent, the capital, to get my Turkmen visa. I took the night train and was immediately reminded of why I dislike public transport. The air conditioning didn't work, and I sweated more in that sauna on wheels than I ever do on my bike. I staggered off the train in Tashkent dehydrated and exhausted. It was a day of typical Central Asian bureaucracy; the Turkmen embassy was staffed by security guards with a palpable contempt for visa applicants, and by diplomats whose idea of an early morning at the office meant strolling in around 11 am. I did manage to get the visa eventually, and then made a mad dash for the airport, where I hopped a flight to Khiva with seconds to spare. It cost me my Swiss army knife, though, stolen by one of the slimy "fixers" who stalk the the airport on the lookout for tourists to scam. He did, however, get me on the flight long after the gates should have been closed.

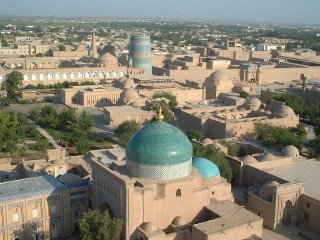

Khiva, a desert oasis town far to the north, in the delta of the Oxus/Amu Darya river, was magical. I only spent an evening and a morning there, but it had perhaps the best historical atmosphere of anywhere I've been so far on this summer's odyssey. It helped that I was there when most of the daytrippers had left, leaving the deserted streets, blue-domed mosques and psychadelic tiled minarets to me. With its intact fortress walls and densely-packed old buildings, it reminded me a lot of Jaisalmer, in India. I fired off a few more rolls of film and then took the long, hot bus ride south to Bukhara and my bike. The 7 police checkpoints slowed down progress considerably, and at each one hawkers would cluster around the bus to sell cold water and snacks. I noticed that the hawkers were not above cheating each other out of clients. There was also a distinct atmosphere of mutual distrust between the passengers and the sellers, with bouts of tug-of-war erupting through the bus windows with cash and water bottles being pulled to and fro as arguments raged over prices. I thought it was a microcosm of Uzbek society.

The ride from Bukhara to the Turkmen border was again hot, featureless and rather dull. I spent the night camped beside the customs post, having been attacked by wasps as a final farewell to the constant sting of being in Uzbekiscam. A few hours of border anarchy, with Uzbek traders trying to run past Turkmen border guards and the commanding officer exploding with rage at them, and I was through into Turkmenistan, following the trail blazed by dozens of Turkish and Iranian trucks on the Teheran-Tashkent freight run.

Turkmenistan is a strange desert mirage of a country, where electricity, gas and water are all free, and gasoline is almost free (1.5 US cents a litre), and huge posters and gold-plated statues of the president dominate the landscape, along with quotes from his Little Green Book. As in Turkmenistan, talking politics is a no-no, as I discovered when I asked my usual conversation-starter "Was life better here under the Soviets?" and the man I was talking to asked me where my hidden microphone was.

It was really, really hot in Turkmenistan; my thermometer registered 43 degrees every day in the shade, and one day hit 48 in the shade and 53 in the sun. I sweated so much that my shorts and T-shirt became stiff with salt encrustations, and I swilled down endless litres of water and soft drinks. The desert was flat and pretty featureless, and the only thing I will remember from the country, other than the heat, were the vast ruins of ancient Merv. Once the largest city in Central Asia, a capital city under some of the Arab Caliphs and the Seljuk Turks and the setting for many of the tales of Scheherazade, it was utterly annihilated by the Mongols and never recovered. Today only the titanic scale of the walls and the occasional half-standing ruin remain to remind visitors what a huge metropolis once thrived there. The walls of the city trashed by Genghis Khan must have been 4 or 5 kilometres on a side, with the older Hellenistic city beside it almost as big. The one surviving structure, a famous mausoleum belonging to the Seljuk Sultan Sanjar, was a huge disappointment as it proved to be a modern reconstruction in gleaming fresh marble with all the historical authenticity and atmosphere of Disneyland. Still, camping amidst the ruins under the stars, with huge walls looming above me, was one of the more memorable nights of the trip.

Halfway across Turkmenistan, I ran into not one but two other groups of cyclists at a tiny truck stop. Jarich and Inge, whom I had met in Bukhara, were there along with a Swedish/Finnish couple who were headed the other way. The Scandinavians had obtained a tourist visa instead of the 5-day transit visa I had, but had to buy an $800 tour to get the visa. They rode their bikes while a bored guide travelled by air-conditioned car and met them at each police checkpoint. They were not pleased to hear that Inge and Jarich had gotten a tourist visa without having to buy a tour!

After four long, hot days I was at the border town of Sarakhs, where I drank my last beer for a while and had lunch with Fernando, a Spanish historian headed the other way along the Silk Road with his bicycle. We exchanged Lonely Planet guidebooks (Iran for Central Asia) and then I headed to the border crossing into Iran.

Iran has been a surprise so far. First of all, it turns out I can cycle in shorts, as long as I put on long pants when I'm off the bike. With 40-plus degree heat every day, this is a life-saver. I've also been surprised that women's dress codes seem to be more and more laxly enforced, with many younger women wearing very short coats (mid-thigh instead of ankle-length) and blue jeans, and with their headscarves barely clinging to the back of their heads. Lots of men with beards and long hair, so I don't feel too out of place, and skin-tight T-shirts are the norm among young men.

Mashhad, a pilgrimage centre, is very busy and expensive, but it's been a good place to rest up after the heat stress of the past week (I feel really quite tired) and buy my plane ticket to Cairo. I have only 3 weeks left, and already my trip seems almost over. I plan to ride along the Caspian Sea coast and then through the mountains to Teheran, perhaps stopping to climb Iran's highest peak, Damavand, along the way if I feel up to it. I'm up on a 900-metre-high plateau here, and although it's still blisteringly hot, the air doesn't sit as leadenly here as it did in the Turkmen lowlands. Still, I think I need to make early starts to beat the afternoon heat.

I hope that everyone's well and taking full advantage of summer. All the best, and have fun!

Cheers

Graydon

No comments:

Post a Comment